A well-respected contemporary philosopher, Anthony O’Hear, writes: “We have no direct access to the world: all our observations of the world and of things in it rest on categorisations and assumptions we impose on what we are observing’ – in other words our access to the world is via verbal and numerical languages.

For most contemporary philosophers, particularly those who might be termed, ‘postmodern’*, there are no experiences that are not mediated by language. They argue that not only is this true, but it is also the case that language, and the categorisation, division and dualism that go with it, largely determine how we view the world. According to O’Hear, if we had such direct access to experience or to the world, that is pure and ‘uncontaminated’ by assumptions, this access would be totally unarticulated and uninformative, and no picture of the world or experience could be constructed from it.

Of course, not everyone would agree. Certainly, in many religious traditions, particularly the traditions of mysticism, a central aim can be ‘direct access to the world’, a direct intuitive experience of ‘what is’ – tathata or ‘suchness’ in Buddhist terminology – mediated, of course, by our perceptual systems.

*

Most philosophers in the 20th and 21st centuries also tend to consider the self as a socio-linguistic construction. What a human subject ‘is’ is constituted by language, culture and environment. The subject is a socio-cultural-linguistic construction. There is either no essential ‘self’ or ‘ego’ that acts as director or autonomous author of someone’s actions and thoughts, or, if there is, we cannot have knowledge of such a self/ego, except through the linguistic, symbolic constructions it presents to us.

The French philosopher/psychologist, Jacques Lacan, articulates this view. Here is Eric Matthews’ summing-up of Lacan’s position: “Human subjectivity in general does not exist, in Lacan’s view, apart from language. This is crucially important philosophically, since it means that one does not exist as a subject independently of relations to other subjects (since language is inseparable from relations with others). Even the very formation of the self is a social construct: one becomes a subject when one learns to say ‘I’”.

In contrast to Lacan’s view, most Buddhist teachers would argue that the ‘linguistic self’ is only one aspect or dimension, of who we are – one strand of the many interwoven currents that make up the fluid contingent self – a self that is continually evolving, growing and changing in the light of experience and circumstance. It is this holistic sense of self that mindful meditation enables us to pay attention to and to explore. Things begin to go awry if we identify too closely with the linguistic dimension – if we come to believe that this is all we are. It is important we keep in touch with the fluid ever-changing currents of the holistic self – not just the chattering dimension.

*

In postmodern philosophy and criticism, there is a tendency to consider the term ‘language’ as meaning words and numbers – verbal and numerical languages. But the term ‘language’ can also denote non-verbal languages – gesture, behaviour, and visual signs and pictures. These non-verbal languages have relevance to Buddhist practice and to Zen in particular. Zen is often referred to as, “a transmission outside language or beyond words”.

From the Zen perspective communication of, and about practice, how to live at peace in the present, tends to be by demonstration, showing rather than telling, pointing rather than theorising. Action speaking more clearly than words.

In the Zen tradition the importance of doing, showing and demonstrating insight can be traced back to the well-known story of the Buddha showing a gathering of students a lotus flower. As he holds it in silence before his audience, one of his followers, Mahākāśyapa, smiles gently. Buddha interprets the single fleeting smile as a manifestation of Mahākāśyapa’s intuitive realisation of the Buddha’s teachings. The Buddha then reminds his students that his teachings are not dependent on words or letters – he is not teaching an academic discipline or a theory, instead he is showing them how to cope with the trials and tribulations of everyday life. Buddhism, the middle way, is a special transmission outside of the scriptures. As a way of being, knowing and doing, it has to be passed from person to person, using whatever methods come to hand. Transmission by words is only one of these methods or dōtoku. Actions, expressions, gestures, including silence and holding up a flower, are others. Needless to say, Buddha entrusts to Mahākāśyapa the task of transmitting his teachings to others. [Agents of uncertainty, p.173-174]

Of course, there is a paradox here. While Zen, and many Buddhist schools, might argue that verbal language is, potentially, a barrier to direct experience (that can be side-stepped or seen-through) there is, nonetheless, a vast Buddhist literature. However, in the case of Zen in particular, there is a non-narrative tendency within Zen utterances, most evident in haiku and other short poetic forms. Stories by, and about, Zen teachers tend to be very short and provocative of action, showing, demonstrating – rather than discursive, analytical or theoretical.

Tilopa, Six Precepts: No thought, no reflection, no analysis, / No cultivation, no intention; / Let it settle itself”.

Lao-tzu: “Those who know do not speak; Those who speak do not know”.

Zenrin Kushu: “You cannot get it by thinking; / You cannot seek it by not-thinking”.

Dogen: “Cast away all speech. / Our words may express it, / but cannot hold it”. [in Hamill & Seaton, 2007]

Issa: “… he teaches without moving his tongue”. [ibid]

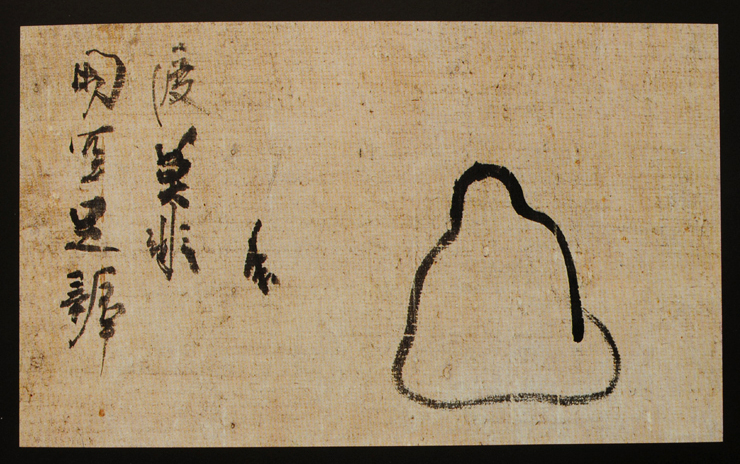

In a painting by Nobutada (1565-1614), Bodhidharma is beautifully evoked with a single line of the brush, next to which are these words: “Quietness and emptiness are enough / to pass through life without error”. [in Addiss, 2018]

There are reasons why silent meditation, (‘silent illumination’ in Zen and silent prayer in Christianity) have been so highly valued – mindful meditation constitutes a silent space in which verbal and numerical languages can be clearly observed as what they are – artificial constructs for categorising, dividing-up, analysing and re-presenting, the fluid, interdependent and interpenetrating processes that constitute the universe. In this way, verbal and numerical languages can be seen-through and let go of, releasing us from the reifying ‘domination of linguistic discourses.’ Freeing us, for a time, from the endless chattering, habit-driven, reactive, clinging forces that otherwise drive our monkey minds. When the chattering mind quietens down, our experience of the world is often vivid, fluid and crystal clear. The chattering is not a necessary agent of experience, it is of peripheral importance. When we let go of the reactive clinging chatter, we are at peace with how the world is, and how we are.

There are parallels here with ideas and practices of the early Greek sceptics, particularly Pyrrho:

From a sceptical point of view human history can be seen as being littered with conflicts fought in the name of dogmatic truths, or false certainties, of every persuasion. If we are to be free of error, to be free “of the domination of linguistic categories” we have to be open to the indeterminacy of things, the awareness that all things are without essence or self-existence. This state of actuality, the sceptics refer to as aoristia, “lack of boundary or definition”. This is very similar …. to what Buddhists refer to as sunyata, or “emptiness”. McEvilley points out that the indeterminacy of things makes them ungraspable in epistemological terms. We cannot define or categorise or assign truth-values to what is indeterminate and indefinable. This ungraspable, ineffableness is what the sceptics call akatalepsia. [Agents of uncertainty, p.96]

Just as the aim of the Buddha was to find a way of living at peace, and peacefully, so the goal of the sceptics was to live in ataraxia – living undisturbed by, but awake to, the vicissitudes of life – imperturbable, equanimous, at peace.

* By ‘postmodern philosophers’ I would include: Ferdinand Saussure, Jacques Derrida, Richard Rorty, Jean-Francois Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, et al.

References

Addiss, Stephen. 2018. The Art of Zen, Echo Point Books.

Danvers, John. 2012. Agents of uncertainty: mysticism, scepticism, Buddhism, art & poetry, Rodopi.

Hamill, Sam & Seaton, J.P. eds. 2007. The Poetry of Zen, Shambhala.

Matthews, E. 1996. Twentieth-Century French Philosophy, Oxford University Press.

O’Hear, A. 1991. What Philosophy Is: An Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. Penguin.

O’Connor, D.J. & Carr, B. 1982. Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge. Harvester Press.