In order to demonstrate how Buddhist insights into the human condition have parallels with insights and analyses in the history of Western thought, we’ll look at a few examples. Given the need for brevity I will be skimming over complex arguments and issues. For further information please see the bibliography below. [Note: Buddha c.490-c.410]

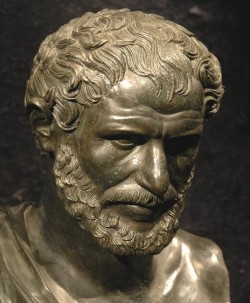

Heraclitus (c.540-c.480 BCE)

Notorious for the obscurity of his writing (known only from 100+ fragments) Heraclitus has had a profound impact on Western philosophy, and his thought seems particularly relevant to life in the twenty-first century. There are a few key features of Heraclitus’s thinking: that everything is in flux, like the constant flow of a river; that ‘all things are one’; and that all arguments, judgments and views are relative.

In suggesting that ‘you can’t step twice into the same river’, Heraclitus provided a memorable image for his thesis that everything is in flux – nothing stays as it is for long – everything is in process, motion and change – ‘the sun is new every day.’ This is a fact of existence and human beings need to confront this fact and learn to live with it. [Note the echoes of Buddha’s emphasis on impermanence – anicca.]

Although Heraclitus suggests that there is a unity to all things, this unity is a unity of opposites and differences in dynamic ever-changing equilibrium – the world is simultaneously one and many. He uses the image of fire, flickering, consuming and transforming – a universe of opposing energies that counter-balance each other. This interdependence [again note the Buddhist connection] means that all things should be considered as relative: ‘the way up and the way down is one and the same’; ‘cold things become warm, and what is warm cools’; ‘in the circumference of a circle, the beginning and the end are common’. Day and night, living and dying, are bound together in mutual dependence – take away ‘night’, and we take away ‘day’; take away dying and we take away living. This relativity and interdependence, this unity of opposites, also applies to our value judgments: ‘good’ only exists in relation to ‘bad’ – and notions of good and bad differ from place to place, time to time, and person to person. In order to be wise, we should stand back from our own limited viewpoint/judgment and see things from a more detached perspective. [Note the affinity with Buddhist ideas about interdependence, causality and relativity]

Heraclitus also pointed out that ‘this world, which is the same for all, was made neither by gods or by men; it was ever, is now, and ever shall be an ever-living Fire, forever kindling and going out.’

Epicurus (c.341-c.270 BCE)

The most thorough outline of Epicurus’ thought is in Lucretius’ epic poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things – c.50BCE). Epicurus takes a theory about atoms, first suggested by Democritus (c.460-c.370), and develops it into an eloquent theory of how the universe is structured. In order to be brief, I’ll list a few of the most significant features of Epicurus’ thought – as described by Lucretius.

- Everything is made of invisible particles (atoms) – constantly in motion, gathering and separating in everchanging structures and forms

- The elementary particles of matter are eternal – permanent building-blocks of everything that exists

- All particles are in motion in an infinite void – there is space for movement, even between atoms in an apparently solid form

- The universe has no creator or designer

- All things come into being as a result of a ‘swerve’ – leading to collisions of atoms that generate endlessly variable forms – nothing is predetermined (eg. by fate or gods). We can act as we wish within a framework of motion, chance and impermanence.

- Humans are not unique

- The soul dies – being made of the same atoms as everything else

- The highest goal of human life is freedom from pain (pleasure) – achieved by being able to reflect on our cravings and desires with equanimity and equilibrium

- The greatest obstacle to pleasure is not pain, it is delusion – the delusion that our desires are satisfiable

- Understanding how the world is, generates deep wonder.

Note the affinities with Buddhist thought – and how Epicurus anticipates ideas and approaches found in modern science.

Bibliography

Heraclitus by A. A. Long – in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol 4, 1998.

The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt – Vintage, 2012 – excellent account of Lucretius/Epicurus.